Curtailed ambition

The year of efficiency heralds a longer chill for publishing

Hi,

I’ve been thinking lately about how we are between eras in lots of areas. It’s always hard to pinpoint when one era gives way to the next. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank appears poised to end a remarkable run for the tech industry. Nothing lasts forever, even if our natural impulse is to assume it will. The messy transition to a more austere environment will be a messy affair, that’s for sure.

First, a message from The Rebooting supporter House of Kaizen

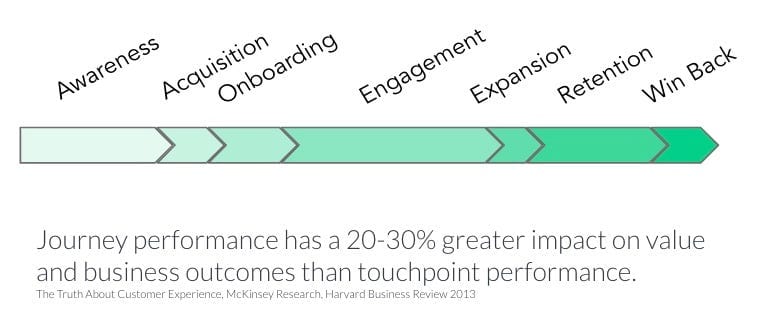

House of Kaizen is now offering a workshop on their Subscriber Growth Framework, which they've used to help many top publications achieve sustainable net-growth. I attended the last one and came away with a framework for thinking through subscription strategy for The Rebooting. House of Kaizen is holding a new workshop for leadership teams at publishers to learn how to implement a customer-centric framework for sustainable growth of subscription and membership revenue. It will be held virtually, on March 20 and 21, and runs for two hours each day, from 11am to 1pmET. Registration closes on March 18. If you use the code REBOOTING at checkout, you’ll get 20%.

Diminished prospects

Without a doubt, digital media is between eras, moving out of the ad-driven scale models into something smaller, arguably less ambitious, and suffering from its own identity crisis.

Before Rafat slaps me down, no, not all media businesses. Troy at has often spoken of how digital publishing in general struggles without a clear goal to optimize to. Right now, it’s hard to identify a large-scale model that’s working outside of the SEO cartels. If the previous era was marked by companies swinging for the fences, the future will be a lot more small ball.

The news part of the sector will always attract new entrants, no matter how daunting the prospects. Jimmy Finkelstein, formerly CEO of The Hill, plans to rival CNN with a new general news publication called The Messenger is also arriving to a different reception. It’s always a fool’s errand to judge a product by how people describe it, since most of the magic is in execution. Still, it’s hard to see the sustainable business prospects of an ad-driven general news publication, no matter if it’s positioned “in the middle,” which generally means center-right. There’s a whiff of nostalgia in how Jimmy describes it:

“I remember an era where you’d sit by the TV, when I was a kid with my family, and we’d all watch ‘60 Minutes’ together. Or we all couldn’t wait to get the next issue of Vanity Fair or whatever other magazine you were interested in. Those days are over, and the fact is, I want to help bring those days back.”

The thing about the past is it never comes back.

I’ve known Jimmy for many years although not particularly well, even though I’d worked for a company he owned. I’d hear from him every time we covered Politico at Digiday. He’d tell me The Hill had bigger ComScore numbers. It was something of a tradition we had. I did a podcast with him in 2019 at his Midtown office once because he refused to go below 14th Street. I noticed something familiar at his office: A framed photo of the Adweek relaunch issue from 2011, when Jimmy was part of an ownership group that took Adweek off Nielsen’s incompetent hands.On the cover, which regrettably was published with a typo, was a familiar scrawl, congratulating Jimmy on the relaunch and adding: “You need to cover the hottest brand around: Trump!” That he became president a few years later should eradicate any imposter’s syndrome anyone has.

I worked for Jimmy and his lieutenant Richard “Mad Dog” Beckman when he owned Adweek, although I mostly kept quiet in my cubicle as a survival strategy. I can remember when Beckman was introduced as CEO to a rattled group that was traumatized by the scorched earth of the post-financial crisis. I asked how he planned to deal with the reality we had a business model dependent on analog dollars when our audience was all in digital channels like blogs, sites and newsletters. I was told the plan was to be “multiplatform.” That didn’t inspire confidence, not to mention the Mad Dog stories from a 1990s era of publishing that in 2010 already seemed from a completely different time. The swashbuckling boys-will-be-boys shrug at executive misbehavior is mostly a thing of the past, thankfully.

I told those considering joining The Messenger the obvious: It was a big bet, and like most risky endeavors, the chances of it working out are long, even with $50 million in backing from various rich people in finance. These days, it’s hard to imagine any venture investor touching the media business. There’s a reason more media companies are rationalizing their decisions to turn to Middle East autocracies. And that’s just because the market now is so different than when ambitious digital media companies launched in the mid-2000s. Semafor is fascinating to track because the ambitions to build a global news organization from scratch are a throwback to a different time.

The previous era digital media was a game of jumping from one burning platform to the next. A longtime exec once rued how the game was piling into a new area that was hot and without standardized measurement in order to make hay while the sun shines – and before the measurement catches up. Then move onto the next one. On The Rebooting Show, former Bleacher Report CEO Dave Finocchio and I discussed the Bleacher playbook and how he plans to tweak it for his new content company – Dave sensibly eschews the term publisher – focused on climate change, The Cool Down. Many of the tactics that worked in those days have worn out. The idea of basing a publication entirely or mostly on advertising was a default, and the opposite is now true. The Messenger is almost contrarian by taking a seemingly old-fashioned approach of building large audiences and relying on ad sales to support an ambitious goal of having 550 journalists in a year.

That strategy is breaking down. BuzzFeed’s business is valued at less than its projected annual revenue. The strategy Jonah Peretti feels out of this familiar playbook of leaping onto what’s hot: creators and AI. That’s while BuzzFees’s core business continues to deteriorate. There’s little doubt that the weight of publishing has swung to individuals. In retrospect, what Bill Simmons has done with The Ringer is something of a prototype. He understood early that individual stars in a collective is a powerful combination. BuzzFeed, on the other hand, has long struggled to be a talent collective. Complex, one of its acquisitions, did a better job, establishing individual-led franchises like First We Feast and Hot Ones.

On AI, BuzzFeed again was an early mover as it has been traditionally. For years, BuzzFeed served as something of the R&D lab of digital media: Leaping onto opportunities early while its peers waited to see what worked. The initial AI quiz game BuzzFeed released – well, try it yourself. My guess is the splashy early efforts in AI will be more about PR than developing a competitive advantage.

After all, BuzzFeed got a big stock bounce over a simple announcement of using AI, only to fall back into delisting territory. The old playbooks are always tempting, as is the case with the hallowed MOAR CONTENT approach that’s being pushed. Yes, if you publish more, you are more likely to rake in more traffic. Ultimately, more supply doesn’t create more demand. The pandemic provided publishers an audience stimulus package that’s being unwound, leaving traffic hungry publishers like the admirably the-name-in-on-the-tin UK news publisher Reach warning of an “attention recession.” Generals tend to fight the last war.

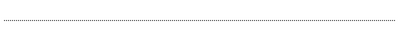

Deconstruction is the fate of many publishing conglomerates. The scale bet has utterly failed. That much was clear long ago. The bet on consolidation has also come up short. BuzzFeed’s purchases of Complex and Huff Post hasn’t given it much of a competitive advantage in the market. The same can be said at Vice, which scooped up Refinery29 in 2019 for what now looks like an absurd $400 million. One Vice suitor, Group Black, wants the entire company for $400 million.

The company’s new co-CEOs – has that ever worked? – are doing their first interviews since CEO Nancy Dubuc departed. They have a tough job. The company has very publicly been unable to sell itself for a while now. And switching to two insider CEOs speaks more to a holding-pattern strategy. The new company chiefs, Bruce Dixon and Hozefa Lokhandwala, introduced a “new” brand positioning of Vice as “for everyone else.” A collection of every niche imaginable invariably becomes general. If we’ve learned anything from the previous era it’s that trying to be all things to all people is a mistake. It’s unclear how Refinery fits into this vision, particularly since it is well on its way to the hospice care phase of many publishing brands when they’re milked for their SEO juice with a robust affiliate operation. I suppose everybody else needs sheets too.

The “winners” of the last decade were not BuzzFeed, Vice, Vox et al, but more “boring” SEO businesses like Dotdash, Future, Red Ventures and Ziff Davis. (In an interesting turnabout, Johan’s former lieutenant Jon Steinberg is now running Future, which has a nearly 12x valuation than BuzzFeed. Jon was right that BuzzFeed should have sold to Disney in 2014.)

Email newsletter companies have also been bright spots. But email-oriented publishers appear destined to be niche. There is nothing wrong with that. Small is beautiful, etc. But the rapid expansion of Morning Brew during the heady days of late 2020 and 2021 appear in retrospect misguided, as Simon Owens detailed. The company has cut deeply into its employee base through two rounds of cuts the past four months. Expanding beyond email has long proven difficult. Ask The Skimm, which was an inspiration to many of the current crop of email-centric publishers but which has also struggled to make a mark beyond email.

The email playbook of spending heavily on customer acquisition and manage lifetime value to create margin will also run its course, even for the dozens of newsletter trying to be the Morning Brew of AI. Email is great, but it has problems growing. There’s limited surface area, as Troy would put it, and being good at email has proven difficult to translate to other formats. Instead, email newsletters appear best for solo and artisanal affairs. That’s why a company like Beehiiv has so much promise. I made a small investment in it, and Tyler is building a formidable business catering to the artisanal end of the media market. (He gives me shit for always talking about Substack, so I hope he’s nice to me at tonight’s happy hour.)

The “hottest” publishers are smaller affairs like Punchbowl, which has gotten the attention of Politico as a true rival for the small but lucrative niche of corporate affairs advertising married with B2B subscriptions. Punchbowl by all accounts has executed great and remained lean, relying on a small group of reporters vs flooding the zone like The Messenger plans. There are already imitators attempting to pull off a Punchbowl-style approach for niche areas like state governments. These are sensible endeavors without needs for massive injections of capital and the long time lines for generating return on that capital. The mood music has changed.

The reset expectations in the tech sector will filter down to the media business, that’s the direction it always goes. The previous advantages of scale will more often turn into liabilities. This is a good time as a publisher to have a low cost base, flexible model and more measured definition of financial success. There haver never been more opportunities to build $10 million to $50 million nicely profitable publishing businesses, but the billion-dollar dreams aren’t happening.

Automation is just a tool, not a threat

Smart publishers will continue to find ways to automate in order to become more efficient. Commerce content takes center stage when it comes to boosting incremental revenue for publishers. But getting results that affect your bottom line can be challenging. Impact.com’s Trackonomics has the five ways to improve commerce content through automation.

Recommendations

The Cool Down is taking an interesting approach to catering to climate-conscious consumers. On The Rebooting Show, I spoke to CEO Dave Finocchio about the opportunity to build a mainstream media brand around climate. Get the episode.

Check out the People vs Algorithms podcast, where I took up the populist narrative around the collapse of SVB as yet another example of supposedly know-it-all insiders coming up short and shifting blame when what they thought were risk-free bets turned bad. Alex was more even handed, and Troy seemed bored by the issue. But it was a good conversation, really.

Axios canned a reporter for a snarky kneejerk email reply to a press release from DeSantis. Publications will fall all over themselves to appear “fair and balanced,” and this was an admittedly dumb move, but we all make mistakes. Firing the reporter is more about optics than ethics.

The coming austerity era and shifting economics of streaming are going to lead to fascinating strategic choices at both Disney and Warner Bros Discovery. Hulu, in particular, is in play, as it celebrates 15 years since its launch. It’s hard to recall now, but as Jason Kilar notes Hulu was thought by many DOA and frequently derided.

Pressboard by impact.com is used by the largest publishers and brands in the world. From January to December 2022, Pressboard analyzed nearly 12,000 pieces of branded content from over 450 publications, read by more than 100 million people. Find out how your sponsored content measures up. (Sponsored)

Get in touch to discuss sponsorships of The Rebooting. This quarter, we’ve worked with great clients like House of Kaizen, HTL Labs, Omeda, Zephr, Glide, Impact and the Webbys.