Signaling premium

Many of the ways publishers showed they're "premium" are going away

Email is great because you get a direct connection with people. It isn’t that great in that it tells you some, but not too much, information. Please take a few minutes to answer this 10-question audience survey. It should take five minutes and will help in a few ways. One is to sell sponsorships because the information will help show who sponsors can reach with The Rebooting sponsorship programs. The other is to help as I expand The Rebooting. Thanks so much.

Audience-owners are the guardians of user data. By ensuring that it is protected, publishers and advertisers regain their central place in the process of discovering, planning for and activating audiences. Permutive ensures that every targeted ad impression, from open auctions to direct, is based on consented, non-PII, directly-sourced data. The Permutive Audience Platform empowers publishers and advertisers to responsibly activate audiences without any third-party access to personal data.

One of my favorite anecdotes for the oddity that is the media business came in the early pages of Googled, Ken Auletta’s story of the early days of the media businesses uneasy collision with tech. In 2003, Mel Karmazin, then CEO of a still-swaggering Viacom, visited Larry Page and Sergey Brin and learned how they’d built what was basically a perfect marketing engine that matched advertisers to users based on their expressed intent. His blunt reaction: “You’re messing with the magic.” (He didn’t say “messing,” but in the interests of optimization, I’m reluctantly censoring myself to improve email deliverability. Life is full of compromises.)

The media business was built on magic, the ability to manufacture the whiff of exclusivity, quality and cultural cachet that turns a piece of communications or entertainment into a valuable product. In the media business, every publisher assures you they are premium. I never in my career heard someone describe their content as “second rate” or “filler” or “stuff they show at dentist offices.” After all, who’s to say, really?

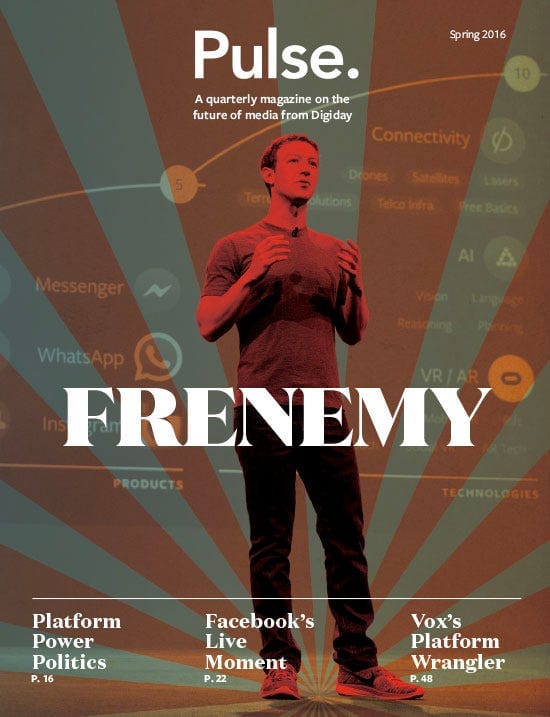

Back in 2016, we started a magazine at Digiday – and for some reason gave it a bizarre name, Pulse. I wanted to do a magazine mostly because of perception. It was an insane media product. We only printed about 1,000 copies the first run, and it was missing for weeks because we used the wrong printer. Somehow, the sales team even sold some ads at what must have been the highest-ever CPM. But a magazine was a way of signaling premium value. I was told it had to pass “the tie test,” meaning that it had to be thicker than a tie. (Speaks to how old school the magazine industry was.) Glossy covers, nice type, good paper stock – these are all classic ways to signal premium value.

Moving media to digital channels erased the concept of scarcity that drove media value. What Karmazin understood is applying math to media would separate the wheat from the chaff, and while John Wanamaker might want to know what half of his advertising is working, the ones selling the other half sure didn’t. Tech also zapped many of the distribution advantages publications had. Google and Facebook flattened distribution and gave control to tech companies, relegating all publishers to the same treatment in a scroll of links.

Publishing brands could still signal premium value through their packaging on websites. After all, good design shows you give a shit. Original photography was another method. Same for illustrations, slick videos on an embedded Brightcove player and incredibly hard to navigate animations. These are “costly signals” as recently identified by Every’s Nathan Bashez:

There are universal principles of visual design that matter across time and in every cultural context. But also, there are certain processes and materials that are seen as premium. This is context-dependent; it changes over time based on technology and economics. When a design uses a premium material like an illustration or an intricate 3D rendering, it is seen as an honest “costly signal” that the company behind it has lots of resources to spare. This, more than grid alignment or proper typographic hierarchy, is the thing that sends a tingle down your spine and makes you think “I should sign up.”

These signals were, of course, weaker than in analog media but still real. Those are being erased now, mostly as publishing moves to different surface areas and what Troy Young calls “full composability”: “Our state of near full composability is the inevitable product of three plus decades of innovation in communication technology, in particular tools that support ubiquitous creation of sophisticated, high quality personal media.”